Location & History

Salmon Creek is located in southwestern Humboldt County, California, and is a major tributary to the South Fork Eel River, tributary to the Eel River

Part I: Location and History

A. Location and Description

Salmon Creek is located in southwestern Humboldt County, California, and is a major tributary to the South Fork Eel River, tributary to the Eel River (Figure I-1). The legal description at the confluence with the South Fork Eel River is T3S R3E S3, and that confluence lies at latitude N 40° 14’7” and longitude W 123° 41’52”. Salmon Creek is a fourth order stream and has approximately 30.1 miles of blue line stream, according to the USGS Miranda, Ettersburg, and Weott 7.5 minute quadrangles. Salmon Creek and its tributaries drain a basin of approximately 37 square miles (Figure I-2.). Elevations range from about 200 feet at the mouth of the creek to approximately 3,000 feet at Gilham Butte, the highest point in the watershed.

Read More of Part I: Location and History

The Salmon Creek Watershed is located near Miranda, California, with year- round vehicle access to lower portions of the watershed from CA State Highway 101 on county roads: the north side of the watershed is accessed by Salmon Creek Road, and the south side by Thomas Road. Most of the extensive road system in the watershed is made up of private roads which are linked to these two county roads.

The major neighboring watersheds are Bull Creek to the north and Redwood Creek to the south, both of which drain into the South Fork Eel River. To the west lies Mattole River System, and to the east are several smaller streams that drain into the South Fork Eel River. The confluence of Salmon Creek and the South Fork Eel River is approximately 56 river miles from the Pacific Ocean, and approximately 17 miles from the confluence of the South Fork Eel and the Mainstem Eel River.

Temperatures in the Salmon Creek Watershed vary dramatically. Summers are generally hot and dry, with extreme maximum air temperatures from 90° to 100°+F, and winters are generally wet and much cooler, with extreme minimum temperatures generally from 20 to 30 degrees F. The average frost free growing season is approximately 200 days, with a slightly longer season in lower elevations near the river and a shorter season at higher elevations. Fog moving up the river from the ocean moderates temperatures along the lower reaches of the creek in both summer and winter.

The most reliable annual precipitation records during the last 25 or so years come from watershed residents. The nearest USGS gaging station is located on the South Fork Eel River at Sylvandale, which is not representative of the Salmon Creek Watershed, parts of which average up to 120 inches of rainfall a year. The rainfall map (Figure I-3) shows average rainfall data for the Salmon Creek Watershed, which ranges from 60” near the confluence with the South Fork Eel to 120” near Gilham Butte. Historical precipitation records from Eureka dating from 1886 to the present have been obtained from the National Weather Service, and these data allow maximum and minimum estimates to be made for that time period.

B. Physical History of the Watershed

The north coast of California is geologically young. The landscape has been shaped by the crushing pressure of the Gorda Plate and North American Plate colliding to the north, and the San Andreas Fault to the south and west. Tectonic movement, although immeasurable in the field on a given day, has impacted the stability of the north coast landscape, soils and streams for millions of years and continues to do so today.

In addition to the effects of plate tectonics, there have been major changes in climate and sea level brought about by shifting glacial weather patterns over tens of thousands of years. Rivers and streams have repeatedly undergone down-cutting phases during cold and wet glacial periods when ocean levels dropped, and stream bed build-up during warmer and drier inter-glacial periods when ocean levels raised. It is believed that before the intense land use impact after European settlement, river systems generally existed in a state of some equilibrium over time, capable of maintaining relatively deep channels despite periodic natural events such as flooding and earthquakes.

Read More of Physical History of the Watershed

Coastal northern California, shown in Figure I-4, is underlain by a series of disrupted rock masses, called “terranes”, that originated as sediments carried on spreading oceanic plates toward our coast, where they were progressively added (accreted) to the continental margin, all of this before the San Andreas fault migrated northwestward along the coast to its present position near Shelter Cove. In the vicinity of Salmon Creek, these several terranes (from east to west: the Central Belt, Yager terrane, Coastal terrane, and King Range terrane) are all part of the Franciscan complex, which is the name given to these accreted rock masses in much of coastal California.

The oldest, most disrupted, and most distinctive terrane in the Salmon Creek Watershed is the Franciscan Central belt (Figure I-5), and this material lends Salmon Creek its pleasing mixture of open grasslands and craggy rock outcrops. This geologic unit is a melange (mixture) of diverse rock types in a highly sheared matrix of clayey rock, likened to a raisin pudding in which the diverse rock types, many of which form prominent crags and buttes, float like raisins in a pudding of sheared clayey materials, which generally form grasslands prone to slow-moving landslides. Bear Buttes, a prominent crag that forms part of the eastern margin of the watershed, consists of submarine intrusive igneous and volcanic rock, whereas Clarks Butte, along the western margin of the watershed, is largely sandstone. Scattered throughout this unit are protruding hard chunks of a remarkable variety of rock types, including high-grade metamorphic rocks (from deep in the Earth), submarine lava flows, and serpentinite (California’s state rock), which is a shiny, generally greenish-gray material that supports unusual wildflowers and abundant poppies.

Gilham Butte, along the northwest margin of the watershed, is underlain by the Yager terrane (named for exposures in Yager Creek, east of Fortuna). This terrane is generally forested and consists largely of mudstone, siltstone, and sandstone, with lesser conglomerate. The Yager generally is less disrupted than the Central Belt, and so does not commonly include hard outcropping rocks of diverse origins or abundant grasslands underlain by highly sheared clayey materials. The Yager terrane underlies nearly half of the watershed in its northern and eastern parts. Uncommonly resistant Yager bedrock, probably largely sandstone, underlies a mile-wide arching band of steep, rugged landscape that extends around the northwestern end of the watershed from the vicinity of Gilham Butte to near Myers Flat.

The southeastern part of the watershed is underlain by very different materials of the Wildcat Group. This stack of young layered sedimentary rocks is familiar from its prominent exposures in the bluffs between Redway and Garberville and in the Scotia Bluffs visible from Highway 101 near Rio Dell. In many places, these young layers of sandstone, conglomerate, siltstone, and mudstone are more-or-less horizontal, and they always are less deformed than the Franciscan terranes they overlie. The sediments of the Wildcat Group were deposited on top of the older Franciscan rocks, apparently over broad area extending at least from Piercy to Arcata. The Wildcat has apparently been eroded from much of this area, but these rocks are preserved in the Salmon Creek-Redway-Garberville area because here they lie along a northwest-trending downwarp (Garberville synform in figure 1) that has protected them from erosion (see cross section in Figure I-5). This downwarp is also responsible for the isolated arm of Central belt that provides the Salmon Creek watershed its distinctive setting of rocky crags and open grasslands largely surrounded by forest.

Reference: Geology of the Cape Mendocino, Eureka, Garberville, and southwestern part of the Hayfork 30×60 minute quadrangles and adjacent offshore area, northern California, by R.J. McLaughlin, S.D. Ellen, M.C. Blake,Jr., A.S. Jayko, W.P. Irwin, K.R. Aalto, G.A. Carver, and S.H. Clarke, Jr.: U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Field Studies Map MF-2336, version 1.0, 26 p., 6 plates, map scale 1:100,000, May 2000.

The upper areas of the Salmon Creek Watershed are deeply incised by tributaries. Extremely high rainfall and steep gradients give these streams a high capacity to transport sediment. The lower reaches of the creek where the gradient is lower tend to hold the sediment in residence longer. There are no prehistoric records of Salmon Creek before European settlers, but it is probable that the lower channels were filled with downed logs, characteristic of lower gradient reaches below steep forested land, with deep pools scoured around the large woody elements and some meanders where natural gravel bars had built up. The earliest air photos (1942) show all of the upper stream reaches and large portions of the lower reaches covered by canopy, which provided shade and thus cool water temperatures. The lower gradient stream reaches would have had prime sites for spawning gravels for salmonids.

Investigation into historic conditions in a watershed can help to understand the contribution of past impacts on today’s problems and to define the potential for maintaining a healthy watershed.

- The Social History of Salmon Creek

- Settlers of European Origin

- New Settlers: 1970 to Present

- Impact of Humans on the Physical Watershed

1. Native Inhabitants

For unnumbered generations before settlers of European origin arrived in what we now know as the Salmon Creek Watershed, the land was inhabited by native peoples who occupied the North Coast Ranges for at least 4,000 years, and possibly as many as 10,000 to 15,000 years. Linguistic evidence suggests that the Athapaskan groups may have come to northern California around A.D. 900. Because of their isolated geographical situation, the Athapaskans have been among the least known to California ethnography. However, there is enough information to indicate that their cultural patterns follow those of most native peoples of northern California: locally independent and relatively peaceful, flourishing in a sort of loose confederation conditioned by similar linguistic or natural environments. (Heizer, 1978)

The native Americans who inhabited Salmon Creek were part of the group that is known today as the Southern Athapaskans. This group is made up of the Nongatl, Sinkyone, Lassik, Wailaki (all of whom spoke dialects of a single language) and the Mattole, (whose language may have been a dialect of this language, or it may have differed enough to qualify as a separate language). The Sinkyone occupied the territory on the west side of the Mainstem and the South Fork of the Eel from Scotia south to Hollow Tree Creek (just south of Leggett). From the Mattole boundary at Spanish Flat south to the Coast Yuki line at Usal Creek they held the coast.

On the basis of linguistic evidence, the Sinkyone have been divided into two groups: a northern group called the Lolangkok Sinkyone (after their name for Bull Creek), who had numerous villages in the Salmon Creek Watershed, and a southern group called the To-cho-be Ke-ah (after their name for Point Delgada at Shelter Cove).

There is more information about the Sinkyone than about most Athapaskan groups thanks to two early ethnographers, C.H. Merriam and P.E. Goddard, who collected information about the northern, or Lolangkok Sinkyone. Figure I-6, showing the Lolangkok territory, is part of a map prepared by Goddard from information he collected in 1903 and 1908 with the help of a Lolangkok Indian named Charlie, probably Charlie Briceland who lived on a 40-acre parcel near the headwaters of Salmon Creek (see Figure 1-10).

The designation Sinkyone is derived from sinkyo or sinkyoko (also sin-ke-kok), the name for the South Fork of the Eel River). The suffixes are ni — ‘tribe of’ and ki or kok — ‘at’, or ‘group at’. The name Lolangkok (Lolonko, Flonko [English corruption], lo-lahn-kok, etc.) is the name for Bull Creek, or a settlement at its mouth (Kroeber 1925:145; Merriam, 1923). The name for Salmon Creek, sah-nan-kok or tse-naan-kok , was also the name for Bear Butte, sah or tse meaning ‘rock’ and nan or naan meaning ‘spring water’ (drinking water as opposed to bathing water).

The lands occupied by the Lolangkok included redwood and fir forests, grasslands, and tracts of oak-woodland forests. Tanoak acorns were probably their most reliable food source besides salmon. Much of their energy was devoted to the tanoak tree, which they managed using fires to limit the oak moth and underbrush. They also spent much of their time gathering and storing the acorns, and preparing them for food. In addition, species of buckeye, manzanita, pine, several varieties of berries, and many other food plants were utilized. Throughout the inland region, large and small game was abundant, with the black-tailed deer and Roosevelt elk most important. There is no doubt of the tremendous importance of fish, particularly salmon, as a food resource in Northwestern California as a whole, and there is evidence that for the Sinkyone fish was a primary resource, even more than game and acorns.

Population data is unreliable for a variety of reasons, but Baumhoff, who used all ecological and other demographic data available at the time (1958) estimated a total for the five southern Athapaskan tribes in aboriginal times as 13,193. He further estimated that the Lolangkok alone occupied an area of 254 square miles, including 43 fishing miles, had an aboriginal population of 2,076, and a population in 1910 of approximately 100 people. (It is interesting to note that the aboriginal population is not entirely different from the current population of the same area today.)

Information indicates that each tribe, subtribe or tribelet may have occupied a drainage region, with its borders therefore represented generally by ridges of mountains separating valleys. These groups spent the majority of their time along the streams and moved to the slopes of the hills and even into the cool forests during the summer, when plant food was readily available. Since summer living was mobile, characterized by temporary settlements, upslope campsites are not nearly as well marked as those used at other times of the year along streams. As a result, most of the known village sites mapped by Baumhoff (1958) lie along streams.

It is interesting to note that within their territory by far the highest concentration of Lolangkok village sites identified by ethnographers was in the Salmon Creek Watershed (although the exact locations of these sites in the Salmon Creek Watershed have been removed from Figure I-6 to protect remaining artifacts). This may be attributed to the variety of geologic and vegetative types found in the watershed. The Lolangkok territory was generally dominated by conifer forests, which were wet, cold and dark in the winter and did not provide a wide variety of food, materials for basketry, or rock suitable for making tools and weapons. In Salmon Creek the intrusion of the Franciscan Central terrane (characterized by open grasslands and rock outcrops) into the Yager terrane (dominated by coniferous forests) gives portions of the watershed attributes that could provide the natives with many of their basic needs: deciduous woodlands and meadows for winter sun and warmth, an abundance of small and large game, a great variety of vegetaion for both food and basketry, and rock outcrops suitable for making spearpoints, arrowheads and knives. And there were plentiful salmon runs.

Following is a very brief view of the Lolangkok culture based on existing information (Heizer, 1978 and Nomland, 1938):

The largest social group was the tribelet, led by a headman, whose privileges and duties included possessing several wives, receiving the largest share of food and property at ceremonies, and the settling of disputes. The main social unit was the simple family; emphasis on wealth was present but not strongly developed; and none of the southern Athapaskans held slaves of any kind. Both men and women could become shamans, who played important roles in the lives of the people. They had frequent dances dedicated to salmon, dogs, coyotes, acorns, with the girls’ adolescence ceremony being the most important, along with an annual dance for world renewal.

The winter dwelling houses were usually circular, and either conically-shaped or wedge-shaped, with pieces of bark or slabs leaned against poles for walls, and doors of swinging or lifting mats, bark, or boughs. Fire pits were in the center of the house. Usually two or more families occupied a single house and shared a firepit. Houses were personally owned, but communally owned land was probably most common among most Southern Athapaskans, including fishing and hunting spots, seed-gathering spots, and trees.

The usual cause for wars or feuds between tribelets or families was revenge or retaliation for murder, witchcraft, insult, or jealousy over women. In general, the Southern Athapaskans were not particularly warlike; they seem to have fought among themselves, but not much with outsiders. The usual weapons of war were sinew-backed bows and arrows, with knives, clubs, sticks, slings, spears, and rocks used in varying degrees by different groups. For all groups but the Mattole, elkhide armor has been reported. No prisoners were taken. Victory dances were common, and compensation for the dead, the injured, and destroyed property was observed. Dances of settlement were also held, after or before the payment of compensation.

There is little specific information about the conflicts between the Lolangkoks and the whites, but there are accounts of massacres of the “Diggers” (as the native peoples were called) by the whites, and those natives that were not killed outright were often kidnapped and then sometimes sold. From 1860 to 1863 numerous younger Indians were “indentured” to Humboldt County citizens under a state law that legalized this form of slavery. Federal troops sometimes attempted to “protect” the remaining Indians by transporting them to poorly run and dangerously unhealthy reservations. By 1910 there were only 100 Sinkyone counted in a population survey.

Salmon Creek apparently provided ideal conditions and the Lolangkok lived for many generations in relative harmony and equilibrium on the land. It is a tragic element in the history of our region that these native people were decimated, leaving so little behind. It is imperative that we protect the sites and artifacts that remain, both out of respect for their culture and for the sake of any future knowledge that could be gained from them.

The first European presence in what is now known as Humboldt County occurred around 1775 with the arrival of Spanish ships in the Humboldt Bay area, and there are records of the Russian-American Fur Company entering Humboldt Bay in 1806. Starting with Jedediah Smith in 1827, there are stories of the occasional fur trapper who found his way through northwestern California en route from the Russian River to the Oregon coast.

However, it was not until the early 1850’s that the first settlers of European origin arrived in the Eel River Basin. A small party of gold miners from the North Fork Trinity River found themselves out of provisions in the fall of 1849 and set off on an expedition to find Trinidad Bay, the elusive harbor of the old Spanish charts, in hopes of establishing a supply route to the gold fields inland. That expedition did finally reach the coast in the Humboldt Bay area, after which the group split up. Half of the group under the leadership of Lewis K. Wood followed the South Fork of the Eel River and eventually traveled south over what was later to become the Sonoma Trail. The journal of L.K. Wood gives a detailed account of a terrifying encounter with 8 grizzlies on January 26, 1850 on the slopes of Bear Buttes (thus the name) just upstream of the confluence of Salmon Creek with the South Fork Eel River.

The following April a fleet of more than 40 ships departed San Francisco headed for Humboldt Bay, filled with shopkeepers, speculators and soldiers of fortune. News of the beautiful, lush country spread far and wide, and within just a few short years communities had sprung up around the bay and along the lower Eel River.

Trappers were probably the first European inhabitants of the back country to the south, but real settlement of this rugged area came more slowly, encouraged by the Homestead Act of 1862 which offered settlers a way to acquire cheap property, and also by the disappearance through violence and disease of most of the area’s aboriginal inhabitants. Those who settled the remote areas like Salmon Creek faced a life of hard work just to transport the necessities of life. The first pioneers packed in a few basic articles by mule or horseback: metal tools, nails, stoves, and kitchenware, some clothing, bedding, and footwear — maybe a few small glass windows, some seeds to plant and a few livestock. After that, they had to find a way of making a living on their own. Every few months, the pioneers might make a trip to the nearest town to replace worn-out tools, clothing and utensils, and to stock up on certain staples that even the hardiest of settlers found it almost impossible to do without: sugar, salt, and pepper, coffee, tobacco, etc. Large quantities of flour were also packed in, for although many settlers raised grain, few had the grist mills with which to grind it. To pay for their staples, the settlers had to raise a surplus of something that could be sold in town (bacon, ham, grain, etc.). If the herds of sheep or cattle were thriving, some could be driven in to be sold.

Trapping played an integral part in the lives of most early homesteaders, and was the major activity and source of income for some early residents. This practice, however, depleted many fur bearing animals, some to the point of extinction.

Salmon Creek was attractive to homesteaders for its open lands suitable for grazing and some limited farming. (A result of these land uses is that the native bunch grasses that grew in meadowlands were mostly replaced by grasses and weeds of European origin.) According to Ernie Rohl (personal communication), there were approximately the same number of homesteaders living in Salmon Creek at the turn of the century (1900) as there are today at the turn of this century (2000). Ernie remembered a school near “Indian Charlie’s” land (Charlie Briceland) in the upper watershed; Charlie took care of the children’s horses while they were in school.

Several surges of settlement occurred, spurred by the continued sale of 160-acre homesteads for $1.25/acre, and by 1900 ranches and farms dotted the prairies and riverside flats of Humboldt County producing meat, dairy goods, fruits, and vegetables. At that time the only community of any size between Garberville and Scotia was the crossroads center of Dyerville, located where the wagon road along the Main Eel met routes from Bull Creek and the South Fork Eel. There were overnight accommodations, called “stopping places” in Pepperwood, Englewood (Redcrest), Myers (Flat), and Phillipsville.

By 1912 the Northwestern Pacific Railroad had crossed the mainstem Eel opposite Dyerville and with the railroad came the loggers. The town of South Fork grew up around the depot and became the shipping point for ranch products of all kinds, tanbark and redwood. By 1914 passengers and goods were rolling between San Francisco and Humboldt by rail, and at the same time the “Redwood Highway” was being constructed for the new automobiles. It was completed in 1922.

Gordon Tosten related this story about his family’s early life in Salmon Creek: Gordon’s grandparents homesteaded near Ettersburg in the Mattole Watershed, coming from the east by wagontrain on the northern migration route through Idaho (where his dad was born) and down the Columbia River Valley. In the early 1920’s, when Gordon was a little boy, his father moved his family from Ettersburg to a flat in the Salmon Creek Watershed near the confluence of three streams known today as South Fork Salmon Creek (called Little Salmon in those times), Tosten Creek, and Kinsey Creek. They dismantled the house in Ettersburg and moved it all the way over to Salmon Creek on a sled and re-erected it. Then his Dad sold the land down on Little Salmon to buy the ranch up on Bear Buttes — and once again moved the house. Gordon remembers tearing the house apart board by board and straightening all those nails. In Ettersburg the family had raised milk goats and had a cheese factory, but when they bought the land up on the Buttes, they turned to sheep ranching. They also peeled tanbark, traveling and camping in stands of tanoak timber (the high-quality tanoak on the Tosten Ranch at Salmon Creek had already been harvested for tanbark before Gordon’s dad bought the land). In addition, they worked on road crews, trapped, and eventually logged, always working extremely hard just to make ends meet and keep the ranch going.

Gordon attended the Oakdale School built in 1928 (Figure 1-7) on the flat just upstream from the confluence of Mill Creek and Salmon Creek, along with Warren Smith’s children (the mother, aunt, and uncles of Harry Vaughn, current watershed resident still living on his family homestead), the Stansberry boys (who lived on the Samuels Ranch), the Thomas boys. It took Gordon about an hour to ride his horse down the ridge and across the old wooden bridge over Salmon Creek, and some of the students had even longer rides. Later other local residents including the Wallans and the Swinnocks attended Oakdale School.

From the memoirs of Gerould Hammond Smith (Harry Vaughn’s uncle): In 1884 Gerould’s grandfather moved from a farm near Eureka to homestead the property where his descendants live today in lower Salmon Creek. Warren Smith (Gerould’s father and Harry’s grandfather) took his bachelor’s degree at Stanford University in 1912 and brought back his knowledge of horticulture and scientific agriculture to develop the by then neglected orchards of the Sunny Slope Farm (Figure 1-8). He also had learned blacksmithing in college, and with his own forge, anvil and smithy tools was able to shoe his own horses, repair his farm machinery, and set tires on his wagons. The family also had a small herd of sheep, a milk cow, a herd of pigs, and extensive vegetable and flower gardens. The barn, still standing, was used for threshing grain and for packing the tons of apples, peaches, and plums that were shipped out each year. When Gerould and his siblings were small, transportation on the farm was by sled, springboard wagon, walking or horseback. They had a Model T Ford garaged across the river for trips to Ferndale at Christmas, but they had to boat the river in the winter to get to the car.

Gerould recalled an early memory of the occasional visit from Mr. Edgeman, who lived with his mother near the headwaters of Salmon Creek (Figure 1-10):

Mr. Edgeman. . . always dressed in campaign hat, pants and coat like a park ranger, and leather puttees. He rode a horse with a rifle strapped to the saddle and led a pack train of two or three horses or mules. He always stopped at the Smith ranch for fruit and visiting after loading up on canned goods, flour, and other groceries at Miranda. (This must have been in the 1920’s.) His mother was nineteen when she went in to the homestead with a friend. They were stalked on the way in by an Indian who was shot by the two girls. I was told that she never once left the homestead after that time until she became seriously ill at the age of ninety. She was carried out because there was no road to the Edgeman home. She was taken out tied into a rocking chair slung between two horses. Dad was one of those who helped bring her out. She knew about airplanes because they flew over their home, but she had never heard a radio.

The transition from homesteads to ranches happened gradually in Salmon Creek as the menfolk from the early settler families left home for longer periods and at greater distances in search of jobs peeling tanbark, building roads, making split stuff, or wherever work could be found to earn a living. This left the women and children at home, and eventually led to the dissolution of the homesteads. Some of the early homestead families bought out the lands of their neighbors, and this led to the formation of the earliest ranches (Figure 1-10).

When Ticki Robinson Early Romanini was five, her mother and stepbrother bought the Kinsey Ranch “out at Salmon Creek. It was about 3,400 acres and they bought it and put cattle on it. The old Kinsey ranch house was there, a big one-room place. No running water inside, no bathroom inside, a big porch around. So, we had our beds out there in the summertime, had a sleeping porch. Huge big fig tree, wonderful figs. And you pumped your water into a barrel out on the porch.” When Ticki was nine, her mother married Pat Brightman, a sheep rancher from Bridgeville, and “he said you could make a lot more money off of sheep than you could cattle.” So, the ranch became a sheep ranch.

Ticki has many wonderful stories to tell about her life on the ranch: “We are just ranchy people. And I just don’t think there’s a better life anyplace or more wholesome than raising everything you have to have, practically except your clothes; and we were raising wool. You know, the life was wonderful.”

The 1921 map (Eureka Historical Society) (Figure 1-10) shows property ownership during this transitional phase, and the larger ranches are roughly in the same configuration as today (Chase is Tosten, Thomas is Thomas, Hillandale and Kinsey is Early, Samuels is Samuels, Hunter is Sunnyside, and Burnell is Chapman). The population was much lower during this period when larger ranches occupied most of the watershed.

Interestingly, Salmon Creek was well-known during Prohibition as the plentiful source of some of the best “bootleg” whiskey in the area, and there are stories of active stills in the watershed into the 1950’s (personal communication, Dave Stockton, HRSP historian).

Before 1947 timber harvesting at Salmon Creek occurred mostly in the lower watershed where redwoods were harvested for “split stuff”: railroad ties, grapestakes, fence posts, and shingle bolts. Kenny Swinnock recalls that when his family first came to Salmon Creek, Mill Creek was “the biggest mess you ever saw. When I was in fourth or fifth grade there (1942) you could hardly even walk-up Mill Creek. There was nothing but big ol’ trees laying in that creek — stakes and stuff all over that creek and there was steelhead everywhere.”

Before 1947 Douglas-fir was not considered merchantable timber. Ticki Early Romanini remembers how she earned money during several summers in her early teens: her step-father showed her how to ring trees on the edges of meadows with a double bitted ax to kill them so he could burn them to increase grazing space for the sheep. She also fell some of the smaller trees herself. She earned a penny a tree, and one summer she remembers earning $34.00. “…So much destruction that we didn’t know what was coming ahead.”

The first local cutting of Douglas-fir began around 1947 as a result of two changes: Post-World War II technology came to the forest: tanks became dozers, and the post-war building boom caused a sky-rocketing demand for lumber. The previously “worthless” fir forests were suddenly of great value, and a new source of employment was created. Following the war land developers began to buy timber (and sometimes, but not always, the land on which it grew), and mills sprang up everywhere. In the 1950’s there were at least seven mills at Salmon Creek. Some of these mills were known as “brush mills”, small mills set up on a temporary basis close enough to a good stand of fir that all the trees cut could be skidded to the mill. When the stand was depleted, the mill was dismantled and moved to another site. At the bottom of Salmon Creek there were two larger mills which cut full dimension finished lumber. Gil Wallan recalls working for 6 or 7 logging seasons in the 1950’s hauling logs on his truck from Salmon Creek to nearby mills.

Timber harvest continued at Salmon Creek through the l950’s and 60’s, until by the late 1960’s most of the merchantable trees had been removed. Land developers began to buy up the ranches and logged-over land to be subdivided in 40- and 80-acre parcels to “back-to-the-landers.” Ticki Early Romanini remembers: “I guess I was probably the last sheep rancher to leave out there. And that was in 1972. Thomas Ranch and Samuels Ranch sold, and they were subdivided. And then some undesirable people moved up there from maybe San Francisco, and they brought a lot of dogs with them. And when they went back to San Francisco in the fall, they’d leave their dogs. And so, it was just… it was a massacre for me. And I think I was the last sheep rancher out there. It really broke my heart.”

Since that time a large portion of the Salmon Creek Watershed has been inhabited by “new settlers”, who are making their own impact on the watershed. At this time the number of landowners in the entire watershed is around two hundred (based on ownership maps from the County Assessor’s office), with an estimated population twice that, which is similar to the numbers at the turn of the century and possibly close to the population of the Lolangkok Sinkyone before their annihilation.

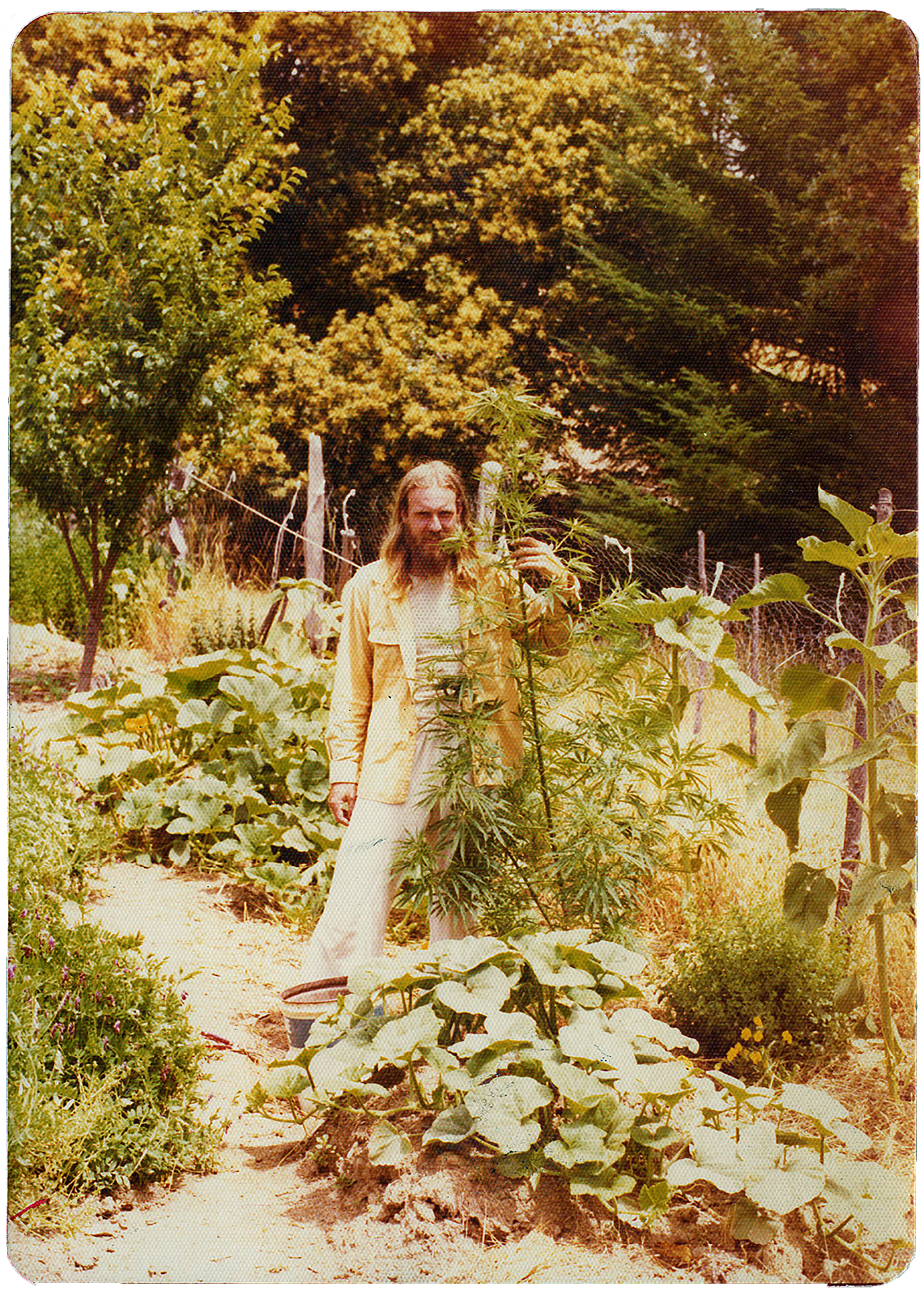

Some of the changes brought to the watershed by the new settlers are: more roads to access homes, outbuildings, firewood, etc.; more vehicle use as many residents drive daily to jobs in towns, schools, shopping, etc.; more water use as more people drink, wash, garden, and enjoy recreational ponds, etc.; more domestic animals which impact the native wildlife. In addition, like the bootleg whiskey of the 1920’s and the logging of the 1950’s and 60’s, the development of an underground “pot” (marijuana) economy in the 1970’s brought an economic boost to the area.

The new settlers too are having a significant impact on the watershed, and this assessment is one more step along the path of understanding how to become better stewards of the land. It must be noted here that this section is brief because of the difficulties inherent in writing objectively about the present: there is no time or space between the story and the storytellers.

The Salmon Creek Watershed has been significantly affected by the forces of nature in combination with the impacts of both Native American and European human inhabitants:

a. Fire: For countless generations Native Americans set fires each year to clear the ground under oak trees to protect their potential harvest from the oak moth. Until fairly recent times homesteaders and ranchers set fires at times to clear forest land for grazing or to clear an area of insect pests. In addition, wildfires have always been part of the landscape history, sometimes burning unchecked for weeks without technology or manpower to control them. Gordon Tosten recalls a fire when he was about 8 (around 1929) that burned a large percentage of the Salmon Creek Watershed, and he recalled that it also burned through major portions of Humboldt County. He said it was so smoky that “your eyes were just crying all the time and you couldn’t breathe. It was so smoky, we lost our apples — they were just too smoky to eat.” The regular occurrence of fires prior to European settlement prevented the buildup of fuels (fallen debris and understory growth), so that when fires did occur early in the century, they burned cooler and slower and tended to clear the debris and to kill only the weak or damaged trees.

In recent years no large wildfires have occurred in the watershed. Intentional or controlled fires have not been used as a management tool at Salmon Creek. This lack of fires in the recent past (which for millennium had been a natural element of the watershed ecology) has certainly changed vegetation patterns and could eventually result in a devastating burn due to the buildup of fuels.

b. Tanbark industry: Another major human impact came in the cutting of nearly all accessible old-growth tanoak for the harvesting of tanbark. This was one of the major industries of the region from the early part of the century and continued until the 1950’s when the development of synthetic tannins made the harvesting of tanbark obsolete. The tanbark was peeled from the fallen trees and sent off by rail or ship to the Bay Area for use in leather tanneries. (There was also a plant in Briceland that converted the bark into tannin extract, making it much easier to ship.) The stripped tanoak were left lying on the ground: “It was such a shame,” remembers Gordon Tosten. “All that solid solid tanoak would have made beautiful lumber. It was solid like fir trees.” There is a story of one of the last Lolangkok Sinkyone in the Briceland area looking around at what had been a tanoak forest; he said, “I feel as if I am seeing my people lying on the ground with their skin cut off.” Although tanoak does sprout, Gordon recalls that it never really seemed to come back the way it was, and it is impossible based on the information available today for us to know what effect the tanbark industry had on the composition of today’s forests.

c. Logging: The impact on Salmon Creek and other northcoast watersheds of logging and the access roads to remove timber is well documented. In Salmon Creek the earliest logging brought the removal of all accessible old growth redwood along the lower creek. Beginning after World War II nearly all of the merchantable Douglas-fir in the watershed was taken. In those days there were few regulations and fewer people to enforce the regulations that did exist. It was common practice to place roads, skid trails and landings in creeks so the logs could be skidded downhill. Roads and skid trails that were neither maintained nor drained diverted water from many natural watercourses, often causing extensive gullies. At that time it was not known how damaging such practices would prove to be to the natural resources; the damage occurred not through bad intentions, but through a general ignorance of the natural processes.

Major flood events often triggered landslides, many on poorly planned and/or constructed roads. Where the land was burned after logging to convert forest to grazing land, even more unprotected soil was left to erode. Slash was left in streams or slid into streams, often creating impassable fish barriers and massive sediment traps. The combination of misguided land use practices and large flood events in 1955 and 1964 caused major aggradation (sediment build up) in most streams in the Salmon Creek Watershed. Aggradation buried or destroyed the natural armoring of the stream banks (rocks, large woody debris, and vegetation) which allowed high flows to scour banks, causing a new round of bank failures and slides.

Although no written records of stream conditions were found, anecdotal stories from longtime residents of the Salmon Creek Watershed as well as evidence based on air photos lead to the conclusion that it was the major floods of 1955 and 1964, following extensive timber harvest, that caused the major devastation that occurred in streams like Salmon Creek. (See Figures I-9 and I-10.) A few of the most common observations about changes in the watershed follow:

Salmon Creek used to have more and deeper holes. Kenny Swinnock remembers, “Nothin’ but holes, one after another…..swimmin’ holes way over your head. I musta’ been at least 5’ tall in those days. It was like that till the ‘55 flood.” (These holes were in the Hideaway Hills area, 2-3 miles upstream from the confluence with the South Fork Eel River.

Gordon Tosten remembers a deep swimming hole near the confluence of South Fork Salmon, Tosten and Kinsey Creeks (approximately 4 miles upstream from the confluence of South Fork Salmon Creek and Mainstem Salmon Creek). There was another “upstream a little bit from Bogus Creek….There was this great big rock and that’s where we’d swim. Now THAT was a deep hole. Musta’ been 15 to 20 feet deep in there kinda’ underneath the shelf of this rock.” (This large rock, approximately 2 miles upstream from the confluence of South Fork Salmon Creek and Mainstem Salmon Creek) is still easily identifiable, and the hole today is only 2’ or 3’ deep.)

Ticki Early Romanini remembers that after the floods “they just didn’t have the pools any more. It was so odd, because there was just a lot of sand and gravel and you didn’t see the great big boulders like you had.”

The biggest change in the creek occurred after the ‘55 flood. “That one flood (1955) changed this creek from all those holes to a huge gravel bar — that’s what it was. You could absolutely drive a 4-wheel drive all the way up the creek. No problem.” (Kenny Swinnock)

That change drastically affected the fish in Salmon Creek. “I remember there used to be three kinds of fish in Carter Creek, the first creek past Bart Swinnock’s place (approximately 3 miles upstream from the confluence of Salmon Creek with the South Fork Eel River) — the kings, the silvers, and the steelhead — all there. The creek was only a few feet wide….. But that flood (’55) ruined it. There was no fish up there for a LONG time after that. Fact, I don’t think I ever caught another fish out of that creek after the flood. In fact, years later it was still (plugged with sediment) clear to the top and running over into the fields. After ‘55 we could still go down to Salmon Creek and catch a steelhead every now and then when things were just right. But they never really came back like they were.” (Kenny Swinnock)

There was more canopy cover. The earliest air photos (1942) of the lower four miles of the watershed show that except for a few wide, low gradient reaches (for example, Hideaway Hills) or where redwood had been removed for split stuff, there was complete canopy cover . All the long time residents interviewed recall big (non-timber) trees along the creek in the early days — many alder and willow, with some cottonwood and a few maples. Gordon remembered “how dark it was down in the creek” downstream from the confluence of Tosten Creek with South Fork Salmon Creek (approximately 4 miles from the confluence of the South Fork Salmon Creek with Mainstem Salmon Creek).

d. Grazing: It is unknown what specific effects grazing may have had on the Salmon Creek Watershed. Grazing can make grasslands more susceptible to erosion, especially if the land is overgrazed, through competition, changes in the grass species, trail networks, and destabilization of hillslopes and stream banks from vegetative loss. Grazing can also put pressure on riparian vegetation, and in some watersheds it has been a major factor in the loss of riparian trees.

e. Subdivision: The cost of building roads was often the main concern of the subdividers when they developed a parcel, so wherever possible, they incorporated already existing logging or ranch roads. When new roads were needed, there was usually no professional planning, which meant that the quality of the layout usually depended on the varying degrees of skill and knowledge of the equipment operators who built the roads. (Indeed, on such steep and/or unstable slopes the challenge of building good roads may have been more appropriate for experienced operators than college trained engineers.) The general result, however, is that subdivision roads are often neither located correctly nor constructed to stand up under the year-round intensive usage to which they have been subjected. Review of some of these roads during the sediment delivery inventory for this assessment shows a number of problems, including undersized and poorly placed culverts, poor alignment, poor drainage, insufficient gravel base, etc.

f. Demographics and Technology: The native Americans were concentrated in villages along the creek for part of the year and were nomadic for the remainder. Family units probably used less water in a day than one flush of a toilet or five minutes of sprinkling a rose garden. There is no evidence of impact that caused erosion leading to sedimentation of the streams.

The homesteaders near the turn of the century were spread out across the watershed similarly to today’s inhabitants. They did not have the cheap technology, however, to divert water from natural watercourses (pumps and black plastic pipe), nor did they have machines to build roads or vehicles to drive on them. Trips to town for supplies were by horseback once or twice a year. Even as late as the 1950’s, the ranchers only drove to town once a week (Swinnock, personal communication), and there were only five families on approximately 18,000 acres, 75% of the watershed.

The single biggest change from the subdivision of large ranches into parcels as small as 20 acres was the development of roads for access to every parcel. Sediment delivery inventories conducted for this assessment on approximately 10% of the watershed found approximately 7+ miles of road per square mile on lands surveyed. Many of these small parcels now have more than one family residence. The easy development of water has enabled today’s families to have large gardens, spring fed swimming ponds, and other conveniences unknown in earlier times. Most families have at least two vehicles and multiple trips to town per family per day are common to allow for jobs, school, volunteer work, recreation, etc. Although past populations of humans may have been near current levels, the impacts on the natural resources was much lower.

g. Pollution: Despite the fact that there is no industrial presence in the watershed, landowners expressed concern about possible pollution from chemicals and fossil fuel spills. Recently several diesel spills in the Southern Humboldt area have been covered extensively on the local news, which has heightened awareness among Salmon Creek residents. There is concern that the number of spills reported is fewer than those actually occurring and whether used oil from generators is being disposed of safely. Although the threat to fish from fossil fuel pollution is acknowledged, residents feel even more concern about the threat to domestic water sources for themselves and future generations.

The accumulation of toxins (phosphates) in our system, due to the use of non-biodegradable soaps, detergents, and cleansers, is also of special concern to some residents. Phosphates are especially toxic to the larval stages of amphibians, like the pacific giant salamander, which were once abundant in our watershed.

h. Fisheries Enhancement Projects: Ironically, even some past fishery restoration efforts by resource agencies have resulted in a negative impact on the fisheries resource in the watershed. The “science” of watershed restoration is always evolving: more understanding leads to the development of new techniques. In hindsight, it has been discovered that the practice of clearing large woody debris (LWD) in log jams to open up blocked streams causes more damage than good because of the removal of critical habitat structures. In addition, the propagation of fish in local hatcheries has threatened the integrity of native gene pools and caused risk of disease to native stock.

In summary, humans are a critical part of our environment, and we have had and continue to have major impacts on our natural environment. The reason for including the watershed history in this assessment is not to point out mistakes or cast blame, but to document the past and learn from it to protect the future of out precious natural resources.

SUNGROWN

ORGANIC

SUSTAINABLE

© Salmon Creek Legacy Farms | Website by Yvonne Hendrix